Stoicism, it turns out, can only get you so far.

I think: did I know this, and forget it? Did wish-thinking take over, so that I dreamt up a luring fantasy that I could just stoic my way out of it? Or did I remember very well, but think I’d give it shot anyway?

I’m not giving up on stoicism. I love it. I do not like the things which stand in opposition to it. I do not like the weeping and wailing and look-at-me-ing. I do not admire grandstanding and drama queening and that nasty strain of competitive grief which is played so ruthlessly by the narcissist. I do not like ululation and holding up the bleeding hands and the playing of the victim.

Everybody has sorrow. Everybody’s heart breaks. Everybody loses someone they love.

There are two voices in my head. (Who am I fooling? There are twenty-seven voices in my head. Sometimes it gets very crowded in there.) But these two voices are speaking the loudest, just now, and they are both saying the same thing.

One says: your mum died. This is the voice which understands well that is an ocean of loss, a great, unmapped expanse of water, almost impossible to navigate. That voice knows that the rogue waves will leave me storm-tossed, and hurl me, breathless and hopeless, to the beach, only to suck me out to sea again. This voice says there is no point trying to fight it or neaten it or pretend that it’s only an ordinary thing which happens to everyone. It does happen to everyone, but at the moment it is happening to me. This voice says, kindly, gently, that I must keep sailing on until that great tempest blows itself out.

The other voice says: your mum died. No need to make a fuss, says that voice, a steely note in it. (This is the same voice that says, when I dress up for a party, well, no-one is going to be looking at you.) Get on, says that voice, and for God’s sake don’t be a bore. Sing another song boys, says this voice, who has been listening to Leonard Cohen, this one has grown old and bitter. This voice is quite useful, in a way. It is the voice which gets me to HorseBack to do my work there, and gets me out to the field to check the water trough and put out the hay, and drives me to make breakfast every morning for my dear stepfather and make bright conversation about world events to cheer him up and keep his mind off it. (As if I could keep his mind off it.)

Another wiser, saner voice speaks now. That voice says: they are both right, and you have to find the balance between the two. Find the balance. Stoicism is not enough, although it can be good and useful and keep one existing in the world. The wild stormy griefs must be let out, from time to time. Probably best if one does that in a nice, quiet, private place, so as not to startle the horses, but they must be given their moment.

Let it out, keep it in. It’s like a push-me-pull-you. Wallowing is no good; self-indulgence is no good; but the thing is real and true and must be felt. Find the balance.

I write all this because I burst into tears in front of the poor stepfather this morning. For all that I believe my job is to cheer him up and be my best self for him, I could not help it. Out they came, the streaming tears. Then I put on my ridiculous hat and made a joke about it. ‘No wonder I am crying,’ I said, a bit watery, ‘when I have a hat like this. It is a truly tragic hat. But it does keep the rain off.’

(I feel there is a life lesson in this, although I can’t quite put my finger on it. It really is a tragic hat, but it really does keep the rain off.)

And we laughed, and I went home to do my work, and said that I would see him in the morning.

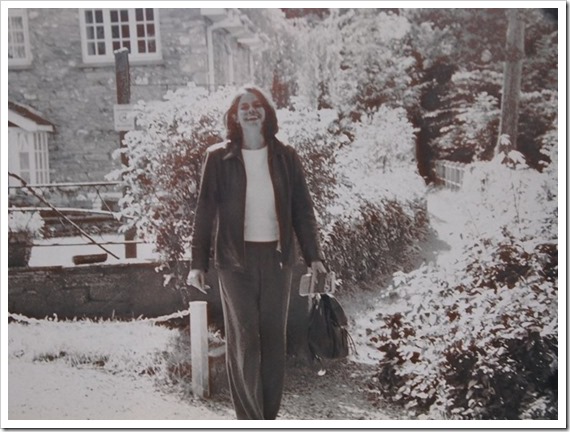

Today’s pictures:

The rain stopped this morning, and the sun shone, and my sweet girls went out into the set-aside to have a little graze. They are so happy and so muddy and so woolly and so absolutely themselves, rooted in this good Scottish earth, shimmering with goodness and authenticity. They are my best consolation, because they are so beautiful and true: