AUTHOR’S SUGGESTION: really only read this if you are as in love with Frankel as I am. For the rest, there is no obligation.

This is a stupidly comprehensive report. I have no excuse, except for the fact that what I saw today is too good not to share.

I am sitting now, in the bar of my little hotel, exhausted but still vibrating with joy, as if every atom in my body were dancing. People are giving me slightly strange looks, as I madly type. Don’t care. DON’T CARE. Because today, I saw Frankel.

The trip to York was a much longer and more complicated drive than I anticipated. I thought it would be a charming sweep across wild Lancashire and Yorkshire moorland. Instead, it was wiggly and a little dull and filled with small towns and traffic lights. So, as I dreamed of the sublime, there was the mundane. I decided this was probably a Good Thing. (It appealed to me, philosophically.)

Once there, finally, I ran about, remembering the charming racecourse. I had not been there since I was fifteen. Wonderfully, it has not changed so very much. There are still white wooden benches, with signs saying: Please do not stand here. Men in panama hats and venerable old ladies were sitting on the benches. But how will they not leap to their feet when Frankel hits the front, I wondered.

I had put my doubts to bed, unusually by forensic examination rather than raw emotion. Take off love hat, put on form hat, and the only conclusion was: nothing can touch him. I had even taken 2-1 with William Hill for him to win by seven lengths or more. It is always important for me to put my money where my mouth is. (I could go into an endless dissection of St Nicholas Abbey and Farhh and the question marks over their heads, but I won’t.)

I was not worried about the trip; I thought Frankel would get it in his sleep. My only fret was the fret I have every time any horse I love goes out on a racecourse. The wrong step, the bump, the unbalanced turn, the bad luck in running, the damn delicacy of those beautiful thoroughbred legs: all these are the things that haunt.

I stopped worrying and went instead to spend my traditional fifteen minutes with the champion. I ruthlessly ignored the race before, even though Frankel’s brother, of whom I am fond, was running in it. I knew the pre-parade ring would be packed, so the only answer was to get there early.

I had checked out the terrain with the man in charge, earlier in the day. ‘Oh yes,’ he said, nodding gravely, ‘he’s coming. They did not send Sea the Stars to the pre-parade ring; they boxed him up and sent him straight to the course. But Sir Henry says Frankel will be here.’

‘Oh, good,’ I said. ‘I’ve come all the way from Scotland to see him.’

The gentleman eyed me speculatively. I could tell he was not quite convinced by the aubergine hair.

‘Sir Henry,’ he said approvingly; ‘he really minds about the racing public.’

Henry Cecil has been having treatment for cancer. He has not been seen on a racecourse for many weeks. I saw him quoted in one newspaper saying: ‘I must be there for Frankel.’ I did not know yet whether he had made the trip from Newmarket or not. I thought he would be pleased that one of the oldest of old school York racecourse men thought so well of him.

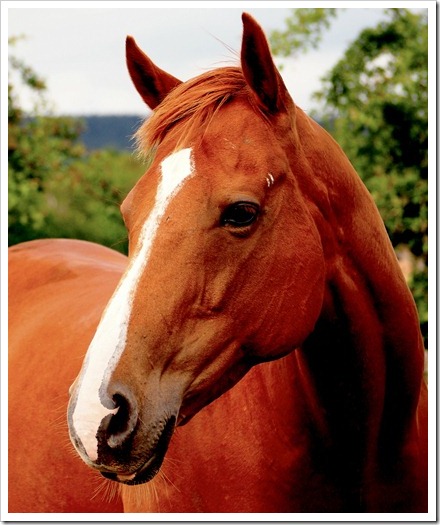

Well, he had sent the horse. The pre-parade ring at York is absolutely tiny. It is hidden away at the far end of the course, under the heavy shade of venerable trees. It is on a slight slope. It is not where you would expect to find a world star. And yet, there he was, with his crowd already four deep, forty-five minutes before his race was due to start. Small children said to their fathers: ‘Put me on your shoulders.’ There was the murmur I remember from Ascot: which one is he, is he here, there he is. A boy of about twelve turned to his mother, eyes shooting out points of light: ‘I got his photograph.’

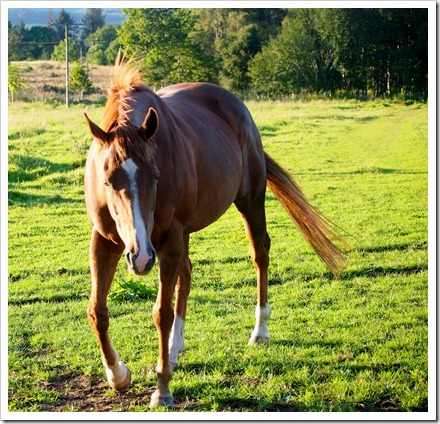

In it all, the big fella walked round, as relaxed as an old hound. This was not always the case. He used to get in a state before races, and needed two lads, one either side, like sentries. They have done something magical with him, at the Cecil yard. They have taught him to put his head down. This very physical act releases endorphins into a horse’s system. All the other colts were carrying their heads high, the veins standing out on their necks. Some of them looked very trained, which is what can happen by this stage of the season. All the early fat is burned away, and the real athlete is revealed. The trick is not to take it too far. (They can be too trained.)

Frankel looked fit as a butcher’s dog, but still wide and strong and bonny. John Francome always says you would not pick him out of the paddock, but I would. I would take him every day of the week and twice on Sundays. I looked into his black, liquid eye. I wanted to laugh and dance like a child. There are very few times in your life that you can stand two feet away from a history-smashing athlete, a best we have ever seen, a once in a generation. It is a crazy privilege.

Having communed with my beautiful fella enough, I ran like a dervish to the best place in the stands. I was only just in time. Even with half an hour to go, the place was jammed. I snatched the last position with an unimpeded view, and sat down on the wall, and took a deep breath. I looked out over the happy crowd, the glittering sun, the emerald green turf. York is a very pretty course. There was a lot of loveliness to distract the eye. Sadly there were not great Aussies to see Black Caviar, as there had been at Ascot, so I did not make friends. There were just two rather stiff gents fore and aft. I tried to put on my special smiling let’s talk about the beauty of Frankel face, but it did not fly.

I had a fag instead.

Then out came the parade. (Should I really tell you all this? I am officially banging on. But every moment of this remarkable day was so extraordinary, and the thing about the columnists and the newspaper writers is that they are only allowed 600 words, and they can’t tell you half of it in that space.)

The moment Frankel appeared he got a rippling round of applause. It was very touching. The clapping was tentative at first; you could sense the crowd thinking they should not upset the fella with too much noise. But in the end they could not help themselves. Glory was in front of them and must be paid its due.

As they could see that Frankel was maintaining him composure beautifully, they let rip. Shouts and yells and applause ran up and down the Knavesmire. Frankel lifted his head and looked as if he realised that there was some business to attend to.

Tom Queally waited until all the other horses had set off; paused, turned, and then took Frankel down in a lovely, bouncing, collected canter. He went to the start like a dressage horse. It brought tears to my eyes, for a reason I could not quite identify. Too much loveliness, perhaps.

And then, for the first time, for all my certainty, I could not stand it. I thought: it’s going to be like Dr Bloody Who. I drove all this way, and I can’t watch. Suddenly, I was assailed by swarming, swamping nerves.

But there was not time for that because they were off. My race glasses were shaking so much I could not see the first five furlongs. Everything was a blur. ‘Frankel’s gone to sleep at the back,’ yelled the commentator. Fuck no, I thought; this is no time to go to sleep.

I hate hold-up tactics. I know they are clever and necessary, but I am scarred for life by Dancing Brave coming too late in his Derby. They kill you like nothing else, if you are trying to watch, with your race glasses shaking like poplars.

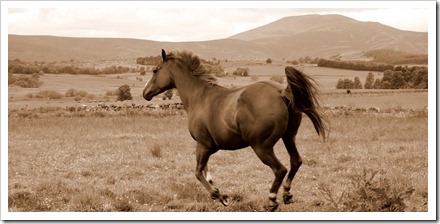

But then, before I died of fright, Frankel woke up. The gears shifted; a small question was asked; a huge question was answered. The turbo kicked; the engine roared; the power unfurled. The crowd went nuts. I don’t know what they were shouting. It sounded like GO GO. It might have been Come on, my son. It might have been Frankel, Frankel.

It might have been Love, Love.

What it meant, as the glorious fella flew home, by four, five, six, seven lengths, was that every single person there was in the presence of greatness and they knew it and they wanted to mark it, with joyous shouts and hands red from clapping and hats literally in the air. (Out of the corner of my eye, I saw one panama shooting across the stands.)

I, as is now fully expected, burst into tears.

It took ages for Queally to pull the horse up. They were practically round at the start before they stopped. They trotted decorously back and I held my breath, desperate that they should come in front of the stands, and not just go back to the winner’s enclosure. Queally had a discussion with an official. ‘Come on,’ I said out loud. The stiff gents gave me a look. Bugger them for a game of soldiers, I thought, missing my Australians.

And there he came, the mighty champion. The crowd rose to him. I whooped and hollered, all shame fled. Tom Queally was so overcome that he fell on the horse’s neck, hugging him with love and gratitude. I rued the day I did not pack waterproof mascara.

In the end, the biggest cheer of all came for Sir Henry Cecil. He was pale and delicate, but wreathed in smiles. He gave Frankel that look I know so well; the one I give my mare. It’s the look of absolute, ineffable love. I am a soppy old amateur. Sir Henry is a hardened professional at the peak of his career. I adore the fact that we give our horses the same look. (Of course at this stage I cannot help remembering that Red and Frankel are cousins.)

Henry Cecil got his cheer because he is whacking away at a horrible illness. He got it because he has been up and been down, and the British appreciate most keenly someone who knows what it is to be up against it. When he was down, the one owner who stuck with him was Prince Khalid Abdullah, who sent him Frankel. There is a ravishing symmetry to that.

And he got his cheer because everyone who follows racing knows that it is one thing having a really talented horse, but it is quite another to keep him sound and keep him interested and place him perfectly and ask him the exact right questions. It is for that reason that unbeaten is such a rare word in racing.

What a pair they are, the young brave and the old warrior. What joy they have given. How they make me lost for superlatives.

I have seen many, many fine sights on a racecourse, but I’m not sure I’ve ever, ever seen anything quite as fine as this.

Lovely photograph by the always talented Alan Crowhurst, for Getty Images.