The work starts to shift. People sometimes wonder why it takes so long to write a book. I wonder why it takes so long, especially when I can bash out fifty words a minute when I’m really cooking. It’s not the word count. That’s not even a sliver of it. It needs a lot of gestation, after the initial words are down. You carry it with you and think and think and think and think. The 153,000 are there, far too many of them, but you can’t see which ones must die. So you walk and gaze and ponder. Then, one morning, you think: ah, the mother must go. So it’s hasta la vista, Mama.

There’s also a ruthlessness which takes time to arrive. At the beginning, the precious manuscript is like a baby bird, every passage coaxed out with tenderness and gentleness. It must be done in a safe private place, with no cruel editing eyes to see.

Then, you get a bit tougher in the second draft. You are coming out into the light.

Then, you have to get absolutely bloody. It’s because of the Dear Readers. You can’t write a book with a readership in mind, thinking I’ll crack that market. If you do that, all authenticity is lost. You have to write the book you want to read. But as the drafts go on, the actual Readers swim into view. They are busy. They do not have time for your self-indulgent flourishes. They want a good story and some good prose and perhaps a little bit of universal wisdom or human condition. They like a laugh. They are not there to watch you do acrobatics.

I’m reading a book at the moment by a very famous writer whose editor is clearly too afraid to wield the blue pencil. Page after page of showing off prose dance before me. A scene which could have taken ten pages rolls on for three chapters, with some very, very writerly writing. I shout in my head: what’s wrong with a good old declarative sentence? If it goes on like this, I’ll never have time to ride the mare.

That’s when the ruthlessness comes in, and why. It is the least the Readers deserve. Oddly, by this stage, it is really not all about you. But this mental shift too takes time. I’m just reaching it now. I feel my sinews harden and my resolve shine.

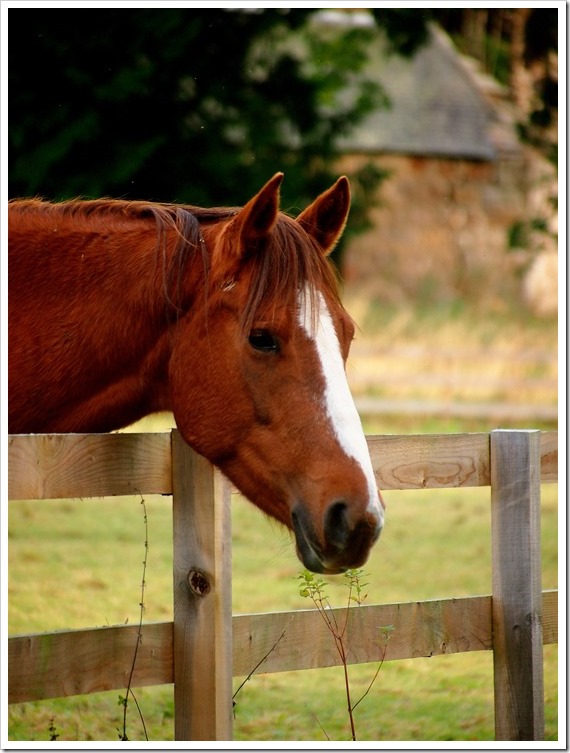

In ordinary life, I make breakfast for my mother, and go down to do the horse. My sister arrives and walks round the block with us. The red mare is delighted since this means that she does not have to do schooling or transitions or anything fancy, but can just mosey along without reins, my hands scratching her withers as she drops her dear heads and sighs with pleasure. We are going so slowly that she can stop and say hello to some children on the avenue. She adores children. She loves the sound of human voices too, so the low rhythms of the Sister and I chatting are her deep delight.

I have no interest in Halloween, but the great-nieces and nephew are coming round later and I make them a chocolate fridge cake. I know they would prefer commercial sweets, but I think of them getting loaded up with sugar and additives and decide that, for the sake of the grown-ups who will have to put them to bed afterwards, some nice black chocolate and nuts and honey and raisins, with no terrifying E numbers or artificial colouring, might be better. I swish about, doing my domestic goddess schtick, making some soup at the same time, something I have not had time for in ages.

The radio is on. A Day in the Life comes on. The first part of it was written about my uncle. He died in a car crash and my father got the call very late and had to drive up the M4, through a black, frigid December night, to identify the body. He left my mother, eight months pregnant with me, at home. He never spoke of that midnight drive. I can’t imagine it. Sixty bleak miles, with a dead brother at the end of it. And then the sight of the body on the slab, that beautiful golden boy whom everyone loved, all the life and promise smashed out of him. My grandmother never really recovered. I’m not sure my father did either. The beloved name was rarely spoken throughout my childhood, as if the very sound of it was too much to bear.

I think of what my dad survived. Not just near-fatal falls on horses, back and neck broken twice, shoulders dislocating like clockwork, an ear ripped half off, but a grief so dark that it could not be put into words. And yet, somehow, he managed to be the life and soul of every party, bringing light with him wherever he went, so that people’s faces lit up and they stood a little taller, basking in the glow of his funny, idiosyncratic charm. It was only at the very end that the demons got him, when he was too battered and tired and defeated to defend himself.

I think of the slow, gentle, private life I live, in these Scottish hills. It is what I can manage. I don’t want to ride in the Grand National or be a shining star. I just want to write some sentences and think some thoughts. I want to watch Stanley the Dog with his stick. I want to walk round the block with my sweet red mare. Lucky for me, that is what she wants too. She was bred to be a champion, but it turned out she did not have the character for it. She is a tender soul. She loves the slow quiet as much as I do. It’s a sort of miracle that we found each other.

Today’s pictures:

Are from the week. They are not the best in terms of photographic quality. But they show the sweetness and that is what I want today.

So muddy and scruffy and happy: