Posted by Tania Kindersley.

My poor students. Today, I suddenly realised, to my horror, that I can be rather abrupt with them. I am galloping along and someone will ask a question or make an observation. They are always good questions and interesting observations. And there should be interjections; my teaching room is a liberal democracy, not North Korea. But I often say, rather quickly, yes yes, no no, very good, and then charge onward.

I think I may have been rude. I hope my mother is not reading this. She will faint, she spent so much of our childhood teaching us manners.

It’s partly because I am trying to cram in as much as I can, rather against the clock. I think also I have had a sense of hurry since all the funerals; yes, yes, no no, on on. Because life is so damn short. But still, there is no excuse for incivility.

If any of them are reading this, I keenly apologise.

Here is some of what I told them today:

Ideas, and where they come from.

The question most often asked of any writer is: where do you get your ideas from?. It is as if people really think there is some kind of ideas shop, like Asda, where you can go and get a job lot, or some special place on the internet based in Lichtenstein which sells them under the counter.

One can’t really say: from life, baby. It would make one sound in need of medication and too poseurish. But the real answer is as simple as that. There is no secret code that you need to punch into the ideas vault. The ideas come from life, from your own experience, from the darker recesses of your own twisty little mind. They come from the news, they come from a snippet of conversation overhead on the underground railway (Alan Bennett famously eavesdrops in caffs and writes it all down), from a couple glimpsed in the distance on a windy day. They can come from emblems: a red balloon, a hopeful tie, a black armband. You can feed voraciously off other writers: what if Madame Bovary had been happy with her doctor? They can come from a mere sentence that wanders into your mind on a dull day: that is the line that starts the whole thing off. They can come from random association or rigorous intellectual curiosity.

The most important question any writer ever asks is: What if? What if a young boy grew up in a strict household where he was beaten every day by his father? And what if he channelled his rage into big ideas, instead of concrete acts? He did not go and bash kids in the playground, but he let his fury at his father, which he could not admit, grow into a spurious theory, about his country and the way it should be run. And what if he developed a craving for power, because he had been powerless? And he went into politics, and just at the time when his entire country felt powerless, so that they, as a group, had some of his own rage? They, he, needed something to stand in for the father, something to rage against, something which was other. So his psychological need, and the psychological need of his country just happened to mesh, at that particular moment in time. And what happens if he made himself the Father, and in the way that twisted psyches do, found himself doing the exact same cruelty that his own father did to him? And suddenly, you have Hitler.

The what ifs do not have to be nearly as big as that. A good story can start from the smallest what if. What if two very different people get stuck on a train? What if a woman gives up her steady job and decides to drive across France? What if a wife finds that she cannot have children?

The what ifs need to come from your own fascinations. Do not let The Fear tell you: no one will be interested in that. There is no subject about which a book may not be written. Perhaps it is as well not to write too much about crown bowls or chartered accountancy. There are some subjects which have wider interest than others. What if I chose the meat instead of the fish is not the most promising beginning. There are few novels written about people who collect stamps or make model trains. On the other hand, even if a subject seems unpromising, if you see fascination in it, and believe in it enough, and write it well enough, you will be able to take your readers with you.

Story.

You can be post-modern if you want, and deconstruct everything until the fat lady sings. It’s a fine balancing act though, and I am quite conservative in liking the traditional beginning, middle and end.

I also have a personal aversion to flashbacks. Some people love them, think they give depth and richness to a story. I have grown so intolerant of them now that I even hate them in films; if something start flashing backwards I actually purse my lips and tut.

The reason is, I think, because I love forward momentum. I want a story to take me somewhere, and for some reason that somewhere feels like it should be forwards. I don’t mind a back flash in a sentence or paragraph: she remembered her grandmother’s rasped voice, or he suddenly thought of his uncle leaving Liverpool in 1955 with nothing but one cabin trunk and his native wit. But just as one is settling into a story set in 1987, I do not want to be dragged back to thirty pages of the flappers.

This is a very personal reaction and one you may ignore. It does hint at a more general point though, which I think does hold. A very august writer, with whom I was lucky to spend some time when I was young and callow, once told me that one should always be aware of the pulling threads that draw a story forward. He mimed with his hands spread wide, as if he literally wanted to drag the reader from one page to the next.

I think the reason this struck me so forcibly is that I learnt dressage as a child. Forward momentum, my teacher shouted. I was always being told to push on. Sometimes I pushed on when I was not supposed to and that gave me a naughty subversive feeling. For whatever reason, the pulling threads drawing forward felt very important.

I do think that flashbacks can stop that forward momentum. They might be fascinating in themselves, add a marvellous, glittering hinterland to the characters, but they are still going backwards. Unless you are very careful and very skilled, you will stall the feeling of progress and movement in the book.

So: a beginning, a middle and an end.

It’s not quite that trite. One of the best tricks I know about story is that you should always start in the middle of the scene. Have the character in the process of doing something: lighting a cigarette, running downstairs, having a fight, being mauled by a sloppy dentist. See them first in action, even if that action is only the act of thought.

So do not think that beginning means that you have to go right back to the beginning, and recite verse and chapter, and map out the family tree, so that everyone knows about great aunt Gertrude and that remittance man from New Guinea.

It’s just that there needs to be a hard place to start, and a good line to open with.

And then you are off, and it does not have to be solidly linear. Even though I avoid flashback, you can dodge about in time and space. I quite like the three years later gambit. If you need to, don’t be afraid of hustling characters forward through time. Get them out of the room, onto the train, up the hill, into the bowels of the ship. You do not have to show them getting into the train, necessarily; have them suddenly in the carriage. France is flashing by the window.

One of the miracles of writing is that small black marks on a page or screen can physically move people through time and space. Don’t neglect that miracle. Use it until its ears bleed.

Character:

Another thing people say is: where do you get your characters from? Again, as if there were a special character shop, where you can go and buy them off the peg.

I think character comes from several different places. In one way, they start with the same What If? that a story does. What if there were a women who always dressed in red and was haunted by the memory of a stranger she once met in Tangier? What if there were a boy from Brixton who ran away to join the circus?

I sometimes think the best ones come from yourself. I often think of characters as like cuttings, from plants. I take a sliver of my own personality, of my own self, plant it in the earth and watch it grow.

Some people love to base characters on people they know. I avoid this, for purely practical rather than ethical reasons. My reasoning goes: you will never, ever fully know another human being. Even one with whom you have lived for twenty years will surprise you. In fiction, you must know every last atom of your characters. So say you base a character on your great aunt Mabel, and then you put her in a traumatic situation like a car wreck or the middle of an ugly divorce, there is the danger that you suddenly think: I do not know what Aunt Mabel would do now. And so you are stymied. It can also lead to self-consciousness. Will Aunt Mabel read this and what would she think?

I quite like a bit of wish fulfilment. What if I were the kind of person who was brave enough to trek the Himalayas or ride the Silk Route? That can lead to a lovely character, with whom you can have fun.

Do not let your own lack of experience confine your characters. You have the precious human gift of imagination. Flaubert was never a bourgeois woman, married to a nice but dull doctor, yet he gave us Madame Bovary. Interestingly, he once said: Madame Bovary, c’est moi. This is quite a profound statement. Jung believed that we all, man or woman, contain the male and female principle, the animus and the anima. So in a sense, Flaubert was right: Madame Bovary, was lui. He was what our modern shrinks would call getting in touch with his female side.

Don’t forget the physicality of a character. Peggy Ashcroft said a wonderful thing about feeling her way into a part, understanding her role. She said: start with the feet. It’s not a bad rule for writing. How do they walk? What shoes do they wear? Do they hate their toes?

Sometimes, if I get stuck with a character, I interview them. I pretend I am Jeremy Paxman and say, I’m going to have to press you on this.

Don’t forget to give them loves and hates, fears and hopes, dreams and night terrors. Give them quirks and foibles and moments of the utterly unexpected. No person is ever entirely predictable. Characters should cohere; but that does not mean they always do what you might expect them to do, in any given situation.

As for the thing of characters taking over: some writers love this and believe in it. Oh, my character suddenly surprised me, they say. Others maintain an iron, Dear Leader grip. I am in the latter school. I make my characters do what I damn well want; I’m not having them skipping about ruining my plot. Nabokov said: my characters are like galley slaves, and I am with him.

Dialogue:

People in books do not talk like people in life; nor should they. If you transcribed a conversation, it would be full of umm and ahs, sort ofs and you knows, broken sentences and unfinished thoughts. Almost no one in life speaks in complete, grammatically correct sentences. If you put real life speech onto a page it would drive the reader, and you, mad.

The secret is to get a facsimile: just loose enough to sound as if it might actually be spoken, but tidy enough to work in fiction. A really good way to learn how to hear dialogue, and I do think it is something you listen for, as you write it, with your inner ear, is to watch films or television series by writers you admire. Aaron Sorkin in The West Wing is a fine example. Some people criticise him because all his characters sound like Aaron Sorkin, from the lowliest secretary to the President of the United States, but it is such sharp, cracking, rhythmic dialogue that I think there is a lot to learn from it.

It is a good thing to try and differentiate your characters by the way they speak, but I do not sweat blood over it. Perhaps one has a love of American slang, or one resorts often to platitude, or one speaks in very short, abrupt sentences. A useful thing to remember is that you can often tell as much about a character from what she does not say as what she does. Terence Rattigan was a master of this.

And a single, very practical note, as close as I get to a cast-iron rule. It is always she said, he said. Never use shrieked or trilled or grunted or warbled. If you are very, very good, I will occasionally allow: she shouted.

A note on language:

Use idioms, slang, figures of speech, metaphors, similes. Read till your eyes bleed is stronger than read a lot. But go carefully. Not everything is like something. Sometimes things are just what they are.

Avoid jargon and management-speak with every last beat of your good heart. It is flat and ugly and often bleached of meaning. Every word in a story or book should, in a perfect world, be earning its keep. Jargon is just a horrid freeloader along for the ride.

Also, remember, the one thing you are aiming for is clarity. If a reader ever, EVER has to go back and read a sentence again, because it is not quite clear, then you have failed. There is a difference between mystery and lack of clarity. You can keep the reader in the dark, doling out information like smarties, making them guess, read between the lines, wonder quite what is going on, but each sentence must be perfectly clear in its own terms. That is why a dangling modifier is the enemy.

There are many grammatical rules you may choose not to obey. It is sometimes perfectly fine to end a sentence with a preposition. It may even be better than fiddling about with to which or with whom; the rhythms may fall better on the ear. I quite often start a paragraph with And or But or So, all of which would make Strunk and White roll about in their graves. The only thing I would say is: know why you are doing it, and do it from purpose, not ignorance or laziness.

There are however, some grammatical rules to which you really should adhere. My number one, gold-plated, ocean-going, fur-lined, no exceptions allowed rule is never, ever, under any circumstance, dangle a modifier.

I do not say this because I am a pedant, although I do have that tendency. It is because of clarity. A dangling modifier always confuses. Also, I happen to think it is aesthetically displeasing, and clunky and clumsy and creaking. But the only real reason is because of the clarity thing.

Here are some actual examples, published in reputable newspapers:

‘Turning the corner, the trees were beautiful.’

This is meaningless. It should be: ‘Turning the corner, she noticed the beauty of the trees.’

Here is one from a travel writer: ‘Sipping cocktails on the balcony, the moon looked magnificent.’

She clearly means: Sipping cocktails on the balcony, we thought the moon looked magnificent, or he beheld the magnificent moon, or she thought the moon magnificent, or I gazed at the magnificent moon.

Because the cocktail sipping must refer to an I or a we, and the I or we is not in the original sentence, it is said to dangle. (In this case, we do not even know if it is an I, he, she or it who is looking at the moon.) Lonely as hell, it attaches itself to the nearest noun, which in this case is moon. What that sentence, as written, actually means is that the moon is sipping cocktails, which is highly unlikely.

I am sure you Dear Readers have never dangled a modifier in your good lives. Just in case you do have any doubts about it, my simple solution is: do not use the walking along, entering the room, turning the corner form to begin a sentence. If you always put the subject in at once, you can almost never go wrong. ‘As she turned the corner, she saw the beautiful trees.’

Before you beat yourself up, remember that even the most mighty institutions get it wrong. I once heard Fiona Bruce, on the BBC news, talking about Beryl Bainbridge. She said: ‘Nominated eight times, the Booker prize eluded her.’

We can pretty much work out what that means, but we have to think for a moment. There is the instinctive feeling something is wrong, and it is. That sentence literally means that the Booker Prize was nominated eight times, which of course is mad. A correct version would be: ‘She was nominated for the Booker Prize eight times, but it eluded her.’

Then there is the misplaced, more than dangled, modifier. A perfect example from the West Wing:

Abbey Bartlet: Women talk about their husbands overshadowing their careers; mine got eaten.

CJ Cregg: Your husband got eaten?

AB: No, my career.

CJC: Yeah, well, I’m on dangling modifier patrol.

There was a bit more, but I’ve gone on too long. Thank you for sticking with. And happy, happy writing.

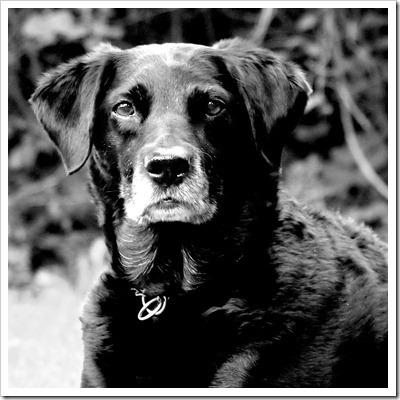

The Pigeon came to meet the students today. She thought they were very fine:

As with all the previous installments, this is just what I need to hear. Thank you again!

ReplyDeleteAnd what did Pigeon make of the students?!

ReplyDeleteEllie - so pleased. You are kind.

ReplyDeleteReturn of the Native - she LOVED them.

I laughed out loud at the bit about ideas coming from Asda or under the counter in Lichtenstein. Whatever makes you think that people don't laugh at your writing? They do, and I did!

ReplyDeleteBeing rude? No, never. No need to apologise. It is hard work to move from concentrating hard on an explanation of modifier dangling to answering a question or discussing a comment and you are doing a wonderful job! Especially so soon after all the funerals.

It was so lovely to meet The Pigeon "in person" - what a gentle, sweet, peaceful dog.

Oh Jennifer J - you are so very kind. You will know better than anyone how fragility lingers, and therefore it is much easier than normal for angst to creep in. Thank you for reassuring. :)

ReplyDeleteI really wish that you had been my creative writing teacher at school. Bad habits are so hard to get out of.

ReplyDeleteRebecca - what a lovely thing to say; thank you. So know the thing about the habits, although I am cheered by the neurologists who say it takes only 28 days to break a habit. You can rewire your brain. Although when I think of my caffeine habit, I think it might be easier said than done.

ReplyDeletePigeon followed you to school.

ReplyDeleteCool.

Thoroughly enjoying reading this. A "sneaky" way to be in on your workshop without "showing up". (What a deal! What a deal!)

XX

28 days to break a habit? I wonder how long it takes to make one?

ReplyDelete